|

AMEZAGA EGUBERRIAK 12-2008 ALZUZA PAMPLONA HOMENAJE A PELLO IRUJO

|

|

| Antecedentes Travesia The Lives of Vicente Amezaga y Mercedes Iribarren |

| . |

When World War II ended and for several years after, the Amezaga family lived separated in three cities. Vicente and Mercedes, and their three children born in America – Arantza, Bingen and Xabier – lived in Montevideo (where they moved from Buenos Aires in 1943), Mirentxu lived in Las Arenas with her uncle and aunts, and Begona lived in San Sebastian with Tia Juli. An important turning point in the life of the family occurred in 1947 when Mirentxu rejoined her parents and three siblings in Montevideo.

It was spring 1945 the end of the war and it was time to think about reuniting us with our parents. The problem was to find a person that could be responsible for us during the long trip from Europe to America. Two years passed and the problem still was unsolved.

My school friends started preparing for their First Communion and I

wanted to receive it, too. But my parents asked me to wait longer so that

perhaps they could participate. So we waited another year. But time passed

and I was eight and a half already so the school started preparing me. At home

I practiced the ceremony millions of times; all my dolls had a Communion. I

took very seriously what was going to happen to me. Religion would be the only

constant in my life and it was and is now a very important sentiment. When the

day came I wore the most beautiful long white lacy dress, a gift from Tia

Juli. The priest would be my uncle, Don Pedro, from Arrate; the date, my

birthday; and the place, my school chapel. It would be a private ceremony,

only for friends and relatives, who filled the well decorated and lighted

little chapel. In front of the altar were two red velvet pews, one for my

uncle and for Aunt Carmen, and one in the middle wrapped in white tulle for

me. It was a great day for me and everyone. We celebrated with a big party.

The absence of my parents was the only shadow. When I knelt in front of the

altar I remembered what my teacher nun told me, that what was about to happen

to me would be the greatest experience I will ever have, and whatever I asked

Jesus for would be granted. So I asked for a lot of things. One of them was

to be reunited with my parents soon. Seven months after my First Communion I

was leaving in a ship from Bilbao en route to America. (In this photo Mirentxu and Begona are in front. The adults behind

them are, from the left, Aunt Elvira, Carmen, Aunt Carmen, Uncle Pedro, Uncle

Ino, Aunt Juli, Uncle Manuel, and cousin Edurne.)

My school friends started preparing for their First Communion and I

wanted to receive it, too. But my parents asked me to wait longer so that

perhaps they could participate. So we waited another year. But time passed

and I was eight and a half already so the school started preparing me. At home

I practiced the ceremony millions of times; all my dolls had a Communion. I

took very seriously what was going to happen to me. Religion would be the only

constant in my life and it was and is now a very important sentiment. When the

day came I wore the most beautiful long white lacy dress, a gift from Tia

Juli. The priest would be my uncle, Don Pedro, from Arrate; the date, my

birthday; and the place, my school chapel. It would be a private ceremony,

only for friends and relatives, who filled the well decorated and lighted

little chapel. In front of the altar were two red velvet pews, one for my

uncle and for Aunt Carmen, and one in the middle wrapped in white tulle for

me. It was a great day for me and everyone. We celebrated with a big party.

The absence of my parents was the only shadow. When I knelt in front of the

altar I remembered what my teacher nun told me, that what was about to happen

to me would be the greatest experience I will ever have, and whatever I asked

Jesus for would be granted. So I asked for a lot of things. One of them was

to be reunited with my parents soon. Seven months after my First Communion I

was leaving in a ship from Bilbao en route to America. (In this photo Mirentxu and Begona are in front. The adults behind

them are, from the left, Aunt Elvira, Carmen, Aunt Carmen, Uncle Pedro, Uncle

Ino, Aunt Juli, Uncle Manuel, and cousin Edurne.)

The summer months flew by quickly in San Sebastian and I would be

joining my parents very soon. I was going to go to America. My uncle knew the

captain of the ship Monte Amboto that would be

sailing to South America with a stop in Montevideo, where my parents were now

living. So they started to arrange my trip to America. I would go by myself.

Begona (shown in this photo c. 1950 in a Basque peasant dress) didn’t

want to go with me even though I tried to convince her. But America was too far for her and there were too many younger siblings to share. She was not

motivated as I was to leave everything and undertake that expedition because

she was living in that world since she was a baby and it was the only one she

knew. With her the trip and the meeting with the whole family would have been

much easier. But even that negative didn’t diminish a bit my strong desire to

be with my parents. Although I was a little bit anxious about going alone for

a month on a ship without knowing anyone, the wish to leave was stronger than

my anxiety.

The summer months flew by quickly in San Sebastian and I would be

joining my parents very soon. I was going to go to America. My uncle knew the

captain of the ship Monte Amboto that would be

sailing to South America with a stop in Montevideo, where my parents were now

living. So they started to arrange my trip to America. I would go by myself.

Begona (shown in this photo c. 1950 in a Basque peasant dress) didn’t

want to go with me even though I tried to convince her. But America was too far for her and there were too many younger siblings to share. She was not

motivated as I was to leave everything and undertake that expedition because

she was living in that world since she was a baby and it was the only one she

knew. With her the trip and the meeting with the whole family would have been

much easier. But even that negative didn’t diminish a bit my strong desire to

be with my parents. Although I was a little bit anxious about going alone for

a month on a ship without knowing anyone, the wish to leave was stronger than

my anxiety.

I went back to Las Arenas after saying goodbye sadly to my sister. My uncle was waiting for me at the train station and we drove home quickly. He was sad. After a while he broke the silence and said to me “You know you don’t need to leave if you don’t want to. You know that don’t you?” I nodded my head and we didn’t say much the rest of the trip. I had decided and I didn’t want to think about it any more.

December 17, 1947, arrived. All the relatives went aboard the ship. After checking my cabin they hugged and kissed me with tears. I felt a lump in my throat but I didn’t cry. I was too scared to cry. The ship moaned her farewell and the tugs pulled her away up the river to the open sea. I stayed on deck watching the city as it became a skyline in the distance. In front of me very soon would be the sea, and more sea. I was a tough nine years old.

Throughout these years, Mirentxu had a strong desire to rejoin her

parents. Unlike Begona, she had memories of their life together as a family,

and she wished more than anything to be able to be with them again. The chief

obstacle was always the dangers in the trip itself. During the war years,

ordinary ship travel in the Atlantic was extremely dangerous. After that, the

problem was finding an adult who would accompany her, and be responsible for

her during the voyage. In these days when long-distance air travel was very

rare, the only option was a month-long sea voyage, and Tio Ino was reluctant to

send the nine-year-old alone on such a long trip. Finally, he sought out an

old friend who was a ship’s captain who agreed to take Mirentxu on the ship’s

next trip to Montevideo. The ship was the Monte Amboto, built in 1928

as a tramp steamer but converted after the war to accommodate 72 passengers.

Tio Ino and Tia Carmen, who were without their own children and who loved

Mirentxu as their own, were saddened to see her leave but they knew that this

step was the best for her. The ship departed Bilbao in December 1947, stopping

in Vigo, Lisbon, and Santa Cruz de Tenerife before reaching Montevideo on

January 15, 1948.

Throughout these years, Mirentxu had a strong desire to rejoin her

parents. Unlike Begona, she had memories of their life together as a family,

and she wished more than anything to be able to be with them again. The chief

obstacle was always the dangers in the trip itself. During the war years,

ordinary ship travel in the Atlantic was extremely dangerous. After that, the

problem was finding an adult who would accompany her, and be responsible for

her during the voyage. In these days when long-distance air travel was very

rare, the only option was a month-long sea voyage, and Tio Ino was reluctant to

send the nine-year-old alone on such a long trip. Finally, he sought out an

old friend who was a ship’s captain who agreed to take Mirentxu on the ship’s

next trip to Montevideo. The ship was the Monte Amboto, built in 1928

as a tramp steamer but converted after the war to accommodate 72 passengers.

Tio Ino and Tia Carmen, who were without their own children and who loved

Mirentxu as their own, were saddened to see her leave but they knew that this

step was the best for her. The ship departed Bilbao in December 1947, stopping

in Vigo, Lisbon, and Santa Cruz de Tenerife before reaching Montevideo on

January 15, 1948.

When they reached Montevideo, the captain of the ship took her to his cabin where her mother and father were waiting for her. Naturally there were tears of joy at the reunion, but in the back of everyone’s mind was the realization that the family was still not complete. Begona had chosen not to come with Mirentxu, and Mirentxu herself had grown up from a tiny two-and-a-half-year-old to nine and a half, and since her parents had not seen her during this time the changes came as something of a surprise to them. And their family had experienced a number of significant changes as well, so it was not at all like what Mirentxu expected. The preceding picture depicts Vicente and Mercedes in Montevideo in the early to middle 1940s. The two photos below were taken in 1948.

The most important of these changes involved her new

siblings. While living in Buenos Aires, Aita and Ama had had their third

child, a daughter named Arantzazu (whom they called Arantxa). And after moving

to Montevideo, they had had two sons: Joseba Bingen and Xabier Inaki. All in

all it was quite a lot for everyone to absorb, and it took a long time for

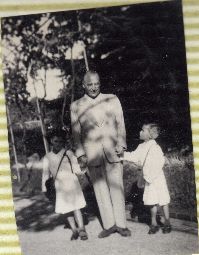

these issues to be worked out as families do. This picture is of Vicente and his

two sons taken in Montevideo on the first day of school.

The most important of these changes involved her new

siblings. While living in Buenos Aires, Aita and Ama had had their third

child, a daughter named Arantzazu (whom they called Arantxa). And after moving

to Montevideo, they had had two sons: Joseba Bingen and Xabier Inaki. All in

all it was quite a lot for everyone to absorb, and it took a long time for

these issues to be worked out as families do. This picture is of Vicente and his

two sons taken in Montevideo on the first day of school.

The other significant changes were in the family finances and the ways in which Aita was able to earn the family’s living. One of the reasons why Aita and Ama had headed for Buenos Aires in their flight from Europe was the importance of the Basque colony in Argentina. A number of important Basque exile figures were already living in Buenos Aires, and they occupied positions of importance both in Argentina and in the Basque Diaspora now scattered around the world. Aita began working in Buenos Aires for a manufacturing firm and the family’s finances began to achieve some degree of stability.

Meanwhile, the president of the Basque Government-in-exile, who by that time was living in New York, decided that they should open a Basque Delegation in the capital of Uruguay, just across the mouth of the River Plate from Buenos Aires. These delegations were de facto embassies, “de facto” because they represented a government that no country recognized as sovereign and independent. Before 1940, there had been only a few such delegations (in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Caracas, and a few other cities) but after the United States entered the war and after President Aguirre reached safety in New York, the Basque Government felt they needed to open quasi-diplomatic relations with more countries in the Western Hemisphere, and Uruguay was an obvious next step. In the spring of 1943, Aguirre approached his old friend, Vicente Amezaga, about taking the job as director of the Basque Delegation in Montevideo, which made him the equivalent of an ambassador in Uruguay. After two long exploratory visits to Montevideo, Aita agreed to do it, and the family moved to Montevideo in September, 1943.

The people of Uruguay received the family so warmly and

their cultural and economic fortunes prospered so much that the Amezagas always

referred to Uruguay as their second home after, of course, Euskadi. The couple

became important members of the Basque community in Montevideo and in the

Basque club, Euskal Erria. Through Aita’s diligent labors, Basque culture was

widely and frequently seen on display in the city. He organized a Semana Vasca

in late 1943 that brought to the city painters, sculptors, writers, musicians,

dancers and many other Basque artists for a week-long cultural celebration. He

persuaded the national university in Montevideo to sponsor a Basque Studies

Program, he taught classes in Basque language and literature, and he eventually

achieved the creation of a Chair in Basque Culture at the university. He wrote

frequent articles for the Uruguayan press, longer articles for Basque

publication, and translations of classics in other languages into Euskera. In

all, it was a magnificent effort that energized the Basque community in Uruguay and won countless friends for the Basque cause in the Uruguayan government. This

photo shows Aita speaking before a conference meeting in the Paraninfo de la

Universidad in Montevideo.

The people of Uruguay received the family so warmly and

their cultural and economic fortunes prospered so much that the Amezagas always

referred to Uruguay as their second home after, of course, Euskadi. The couple

became important members of the Basque community in Montevideo and in the

Basque club, Euskal Erria. Through Aita’s diligent labors, Basque culture was

widely and frequently seen on display in the city. He organized a Semana Vasca

in late 1943 that brought to the city painters, sculptors, writers, musicians,

dancers and many other Basque artists for a week-long cultural celebration. He

persuaded the national university in Montevideo to sponsor a Basque Studies

Program, he taught classes in Basque language and literature, and he eventually

achieved the creation of a Chair in Basque Culture at the university. He wrote

frequent articles for the Uruguayan press, longer articles for Basque

publication, and translations of classics in other languages into Euskera. In

all, it was a magnificent effort that energized the Basque community in Uruguay and won countless friends for the Basque cause in the Uruguayan government. This

photo shows Aita speaking before a conference meeting in the Paraninfo de la

Universidad in Montevideo.

The problem was, however, that the Basque Government was severely short of funds with which to support these efforts and the Amezaga family. Without a territory or a national economy, the government-in-exile had to rely on extraterritorial sources of support. For many years the people in the Diaspora were struggling to make ends meet and were unable to lend their support. There was another source, however, and President Aguirre came to depend almost entirely on it: the United States Government, through the Department of State.

Throughout World War II, although General Franco never became a belligerent country the U.S. regarded Spain as a part of the international fascist movement and treated its representatives as being only slightly more acceptable than those of Nazi Germany and Italy. In the early years of the war, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, established networks of informants throughout the Western Hemisphere to help the U.S. keep track of German, Italian and Spanish agents. The Basque Government offered its services to this effort and was rewarded with significant financial help that became its principal source of funds. As the delegate of the Basque Government in Montevideo, Aita also became the leader of a network of about half a dozen Basque men who gathered intelligence information about fascist agents in Uruguay and passed it on to Basques in New York who then sent it to Washington. The money he earned from this service was a vital part of the family income during the early and middle years of the 1940s.

In 1947, however, U.S. policy swung 180 degrees away from concerns about international fascism. With the beginning of the Cold War, communism became the enemy and Spain, after 1952, became an ally in that struggle. The State Department and the CIA now withdrew financial support from the Basque Government, a step that plunged the exile effort into a major financial crisis from which it never recovered. In Montevideo, the Amezaga family now faced considerable financial hardship with the loss of these funds. Things worsened steadily to the point where Aita decided in 1955 to leave Montevideo and seek an improved financial situation in Caracas.

Let us return to the moment of Mirentxu’s arrival in the Montevideo harbor. Here is how Mirentxu described these emotional moments, and their aftermath.

After a month of crossing many time zones, the perception that I had left something behind grew stronger as I was approaching my destination. I was adjusting a new watch, a gift from my parents on my First Communion, to the proper zone. Just prior to my arrival I felt increased anxiety and fear about the new and unknown world of my family and new country.

The trip was long, a month, but we saw a lot of different places. We stopped at the port of La Coruna, Vigo, where the captain took me to the circus. We navigated through the Canary Islands and we were at the port of Tenerife for several hours. Then we crossed the Atlantic Ocean through a big storm. I remember that before we reached Brazil we had a Christmas celebration aboard ship. We stayed for only a few hours at the port of Bahia. My state of anxiety was growing and I remember after Rio de Janeiro I didn’t want to pay attention to Santos or anything else. At last the day came. Slowly the ship steamed up the Plata River, and the harbor of Montevideo was there in front of us. The date was January 15, 1948, seven years to the day after my parents left Europe from Marseille.

The captain and I together were on the deck looking at the harbor that was coming closer. We were both waiting anxiously for the ship to anchor in port. Feeling alone and desperately searching for a familiar face, I asked the captain “Who are my parents?” Before he could answer, my parents, my five-year-old sister, Arantzazu, and my two-year-old brother, Bingen, were running toward the ship calling my name. Now I was not Merceditas any longer. They called me Mirentxu. For every situation in my short life I had a new name. A little nervous, we exchanged a few words across the harbor to the deck. Then the captain took me to his cabin to greet them in private and to deliver me officially to my parents. The minutes passed slowly, it seemed hours to me. Suddenly my farther appeared at the door followed by the rest of the family and a few friends. My father full of emotion kissed me and hugged me calling me “nere maitea,” (“my dear” in Basque). Then my mother with tears in her eyes hugged me for a long time. She said “You make us very happy!” Then my sister and brother gave me big kisses. Everybody was so joyful but I didn’t react. I felt like my emotions were frozen. I was dreaming of this moment for so long and now that it happened I was having mixed feelings of pride and fear. Pride because I had the courage to decide the cross the Atlantic Ocean by myself to see my parents. To know your parents and younger siblings when you are 9 years old it is not a common thing. I think I had a lot of anxiety to know everybody, but once I did I was ready to see my uncle and aunts again. Everybody was full of intense emotion. Abruptly everything was new, all of it unknown, and I was a stranger in my own home. I lost most of the roles I once played in my own town as a family member (the central place), my friends, my school. Here no one knew me, even my own parents and siblings. I will be nobody, and that thought scared me.

At home was my youngest brother Xabier, eight months old. He was a precious little fat blonde baby. He smiled at me and I started loving him at that moment. The apartment in this beautiful city of Montevideo was situated at 1615 Juan Paullier Street, on the third floor. I went to my room followed by my sister and brother. My sister Arantza was almost 5 years old, a very pretty and precocious one. She was very interested for everything I said and did and she followed me to every place. My brother Bingen 2 years and a half was a beautiful, serene and quiet child with big melancholic eyes.

My crossing the Atlantic changed not only my life but the lives of all those around me, in a drastic way. I was missing so many things, like the music in the streets of Las Arenas, the “Gigantes” and “Cabezudos,” the parades, the floats. Why weren’t there people in the streets at night? Why didn’t we have trips on the train to the mountains? Where were the snacks at the “tapas” bars after Mass? Where were the chocolate and “churros” for breakfast in bed? How about the town holiday on my saint’s day? My uncle and aunts, my friends, my school, where was all that and more that had been a part of my life until now? It took weeks and maybe months before I could adjust to the big changes in my life in all aspects. It was a big adaptation for my parents too because they hadn’t seen me grow up, and now they had a nine-year-old whom they didn’t know. Plus they didn’t have the experience of having a child that age so they treated me more like a little girl, the one they knew, rather than like a girl growing into the teenage years that had grown up during those seven years of separation.

I felt I had been robbed of all the things a child is entitled to,

and I felt envy toward my siblings who had not been abandoned and were well

adjusted in their home. I need to fight for everything that they got for

granted. There was also an age difference between me and the three of them.

They could not be my playmates. Many times I was their babysitter even though

I was only 10. At the same time, my mother was sewing identical dresses for me

and my sister who was five years younger. In this photo, we were preparing to

go to the birthday party of one of my classmates, Marta Tochetti.  But everybody in the family needed to adjus tto

my arrival.

But everybody in the family needed to adjus tto

my arrival.

In our home in Montevideo there was much emphasis on elegance and formality. The style of the furniture was formal and classic. There were many meetings and dinners given for Basque visitors and Uruguayan friends. At the entrance of our home there hung a copy of Francois Millet’s painting “The Angelus,” to introduce the formality of the house. Below the picture was a carved wood chest where my mother kept the linen tablecloths. In the dining room there was a cherry china cabinet that matched the big table and chairs. The living room had a sofa and chairs upholstered with a garnet-colored silk brocade material. Both these rooms opened on to a balcony from which we could see the Atlantic Ocean in the distance.

These photos of the four Amezaga children was taken in 1952 during an outing to the farm, or chacra, owned by a family, the Birabens, whose parents had become close friends of the Amezagas. The family visited there frequently during the summer months and enjoyed immensely the solitude and nature of the place.

The day after I arrived, I awoke early in the morning. The rest of the family was still sleeping. I went to the open window of my new room which I shared with my sister and looked at the houses and surrounding neighborhood for a long time but without really seeing anything. I could hear the moaning of the ships far away and for a moment I wished to go back on that ship again. My mind was confused and my heart was heavy.

Later on my parents took me to see the city. They bought balloons and we went to the Jose Enrique Rodo Amusement Park near the beach. There was another person in my parents’ household, a nice lady whom everyone called “Tata,” who was the housekeeper. She took us to the park every afternoon and she also kept an eye on the children in the evening when my parents were not at home. Before long I would replace her in the evenings. My parents had a very busy social schedule between the Basque community and their Uruguayan friends, and they were away from home several evenings a week.

Living in exile, my father was overwhelmed with the economic and political situation abroad and at home he was absorbed with how to pay the bills of his new responsibility. My mother tried to do her best with her four children and the pain of the one still missing, and helping her husband cope with his situation. She didn’t have the energy or the tools to understand the tremendous change and adjustment that her oldest child was going through at that young age. I was reincorporated into their lives, but because of their being in exile I was another mouth to feed and I felt more that I was in their way. All these feelings were manifested in a variety of ways. I started to have school problems, poor concentration, lying, cheating, and I had all kinds of physical pains imaginable. One moment I felt confident that I knew and understood their love, but the next minute I felt like a foreigner. But at last my parents’ love and my courage overcame every obstacle.

My mother was a very energetic person, always very busy. In the mornings she was at the market. Later on she cooked our meals. She was a very good cook and she did it with the same delight that she bought the food. In the afternoons she did the sewing, knitting, tapestry or whatever was necessary. She was very talented with her hands and she made artistic masterpieces with anything she proposed to do. In the evenings if they didn’t have any social engagements my father would be working at his desk until late and she would be at his side doing any kind of work. She was a very quiet, disciplined and well organized person. She had a great ability with numbers. She told me one day the Stock Market would be a perfect place for her to work. She was a very good administrator, the soul of the house, and she resolved any problem calmly and quietly. I don’t think any of us have her serene personality.

Our apartment was very pretty and nicely

decorated. It was situated in a very good part of the city with access to the

biggest shops. It was half a block from the city’s main avenue, “18 de Julio,”

and two blocks from the big, beautiful park “Los Aliados”. In that park is an

obelisk raised to commemorate the patriots who signed the first constitution of

the country in 1830. The monument was designed by the illustrious poet,

politician and writer Juan Zorrilla de San Martin. The “Tata” took us to this

park almost every afternoon during the hot summer months, and on weekends my

parents took us to the beach. But wherever I went, whether to the park or the

beach, I remember the children staring at me when I talked because of my heavy

accent. To me it was a little bit of a nuisance.

Our apartment was very pretty and nicely

decorated. It was situated in a very good part of the city with access to the

biggest shops. It was half a block from the city’s main avenue, “18 de Julio,”

and two blocks from the big, beautiful park “Los Aliados”. In that park is an

obelisk raised to commemorate the patriots who signed the first constitution of

the country in 1830. The monument was designed by the illustrious poet,

politician and writer Juan Zorrilla de San Martin. The “Tata” took us to this

park almost every afternoon during the hot summer months, and on weekends my

parents took us to the beach. But wherever I went, whether to the park or the

beach, I remember the children staring at me when I talked because of my heavy

accent. To me it was a little bit of a nuisance.

But with the arrival in only one year of two children – Xabier and me – the apartment was now too small, and my parents started to look for a new home even though it would be a little bit farther from the city. Six months later we moved to a new, more spacious house that was between the beach and the downtown area. The new, spacious apartment had a nice view of the sea. The neighborhood was quiet and there was a small park in front of the house where I took my siblings in the afternoon. The school was seven blocks away; the beach, fifteen blocks.

March arrived. It was fall in this part of the world and the month

for schools to reopen. At home we started to talk about that, but I was

afraid. I didn’t like the idea of being with other children, at least not

until I could lose the accent that gave me the nickname “Espanolita” (“little

Spaniard”). I disliked the nickname enormously. Mostly I didn’t like to be

different from them (I didn’t realize that I was unique in more ways than one),

but also because of the anti-Spanish sentiments that my parents or any Basque

exile would have. My parents registered me and my sister in the French

Dominican school, my sister in kindergarten and me in the third grade (even

though I belonged in  the fourth grade). I was proud of having been born in France and my name was the only proof of that, so I wanted to be called by my real name:

Marie Mercedes Jeanne. But in school they called me in Spanish Maria Mercedes,

and my friends called me in Basque Mirentxu, and that was very frustrating in

those years. The first day of school came and even though I was very anxious

because I didn’t know anybody, I would soon make that school my second home.

Later that day all the family went to a photo studio to have a picture taken to

recall the event of the year: my reunion with the family. The photo was framed

and kept in a place of honor in the dining room always. It is the only studio

portrait of my mother with the four of us.

the fourth grade). I was proud of having been born in France and my name was the only proof of that, so I wanted to be called by my real name:

Marie Mercedes Jeanne. But in school they called me in Spanish Maria Mercedes,

and my friends called me in Basque Mirentxu, and that was very frustrating in

those years. The first day of school came and even though I was very anxious

because I didn’t know anybody, I would soon make that school my second home.

Later that day all the family went to a photo studio to have a picture taken to

recall the event of the year: my reunion with the family. The photo was framed

and kept in a place of honor in the dining room always. It is the only studio

portrait of my mother with the four of us.

For my tenth birthday my parents organized a surprise party with a dozen of my parents’ friends and their children. A friend of my parents was invited and he brought movies of Charlie Chaplin. “The Great Dictator” was one of his favorites because it made fun of the powerful dictator of those years, Adolph Hitler. When I got home from school that dark, rainy day, the house was brightly lighted and completely decorated with colorful balloons and confetti. That party was announced in the press the next day as being in honor of me and Xabier, who was going to be one year old four days later. I loved the gifts and all the commotion of that day.

Upon her arrival in Montevideo, Mirentxu was enrolled in the Liceo Santo Domingo, a Catholic school for girls run by nuns of the Dominican order. She arrived in the middle of her third year in school, so the Liceo made her begin the third year over, which perturbed the Amezagas quite a bit. The school and the nuns and the cloistered experience became a treasured sanctuary for Mirentxu as she grew older. The sisters showed her great attention and affection and she began to spend more and more time at the school. Although Aita and Ama were pleased that Mirentxu was a devout Catholic, they felt that she spent far too much time at the school and with the nuns. Below are two contemporary photos of the school, its front entrance and one of its classrooms.

Shortly after I started school my accent was gone and I talked with that sweet, melodious Uruguayan accent. I felt better, but this was only on the outside. It would take longer, maybe a couple of years or more to be like my peers. My parents also didn’t let me forget that they a family in exile “dreaming” of an imminent return to Euskadi. So they took me to the Basque Clubs where I participated in their festivals and dances and I took Basque language classes every Wednesday during all the years we lived in Uruguay. So naturally I felt two different ways of being: at home I felt Basque and at school I acted like another Uruguayan.

My father tried very hard to represent to the

best of his abilities a country that Uruguayanas did not know very well. Among

the many things he did were lectures and public speeches, and he wrote in the

newspapers about the Basques every day. He also taught the Basque language and

culture at the university. In addition to many other authors, he translated

into Basque the works of Shakespeare, including “Mid-Summer Night’s Dream” and

“Hamlet”. This last he finished six months before the coronation of Queen

Elizabeth II, and the Basque Society of Uruguay sent the book as a gift to Her

Majesty.

My father tried very hard to represent to the

best of his abilities a country that Uruguayanas did not know very well. Among

the many things he did were lectures and public speeches, and he wrote in the

newspapers about the Basques every day. He also taught the Basque language and

culture at the university. In addition to many other authors, he translated

into Basque the works of Shakespeare, including “Mid-Summer Night’s Dream” and

“Hamlet”. This last he finished six months before the coronation of Queen

Elizabeth II, and the Basque Society of Uruguay sent the book as a gift to Her

Majesty.

Perhaps for that reason, I was very involved in

the following the life of the English Monarchy. It started as an assignment

from my English teacher at school. I started collecting all the information

that fell into my hands and there was a lot in those days. So I prepared a

play at home mostly for my three siblings. Our presentation in the somber

dining room of our house was attended by a few neighbors. It was the thing to

do at that moment when everyone was talking about this historic event.

Perhaps for that reason, I was very involved in

the following the life of the English Monarchy. It started as an assignment

from my English teacher at school. I started collecting all the information

that fell into my hands and there was a lot in those days. So I prepared a

play at home mostly for my three siblings. Our presentation in the somber

dining room of our house was attended by a few neighbors. It was the thing to

do at that moment when everyone was talking about this historic event.

Aita enjoyed telling us classic adventure stories such as Robin Hood, Jules Verne science fiction, and, of course, stories from the Bible, which he read every night. Our home would have been a happy one had it not been for Begona’s absence and my parents’ forced exile. Neither one tried to assimilate into the host culture but they were always very appreciative of the country that took them in.

At home our religious life was intense. My parents followed the liturgical celebrations. The Rosary was recited in Basque every night and everybody participated. Mass was never missed, except once when an outbreak of polio forced everyone to avoid public places and we listed to Mass on the radio. We usually attend Mass at our school’s chapel. The chapel was always decorated with garlands of greens and beautiful flowers. The nuns’ singing filled the air. Everything was so beautiful that many times it was unreal to me.

Montevideo was the perfect place for the entire family to be. It was a spacious city with broad boulevards, beaches, and an important port. The people of Montevideo were famous for their hospitality and generous friendship. The level of cultural, political and social life of Uruguay earned it the title “Switzerland of South America,” at least until the 1960s. Herds of breeding cattle, bulls, horses and mares multiply freely on the vast prairies and tall grasslands. On the pampas, the unique nomadic “gaucho” (equivalent to the American cowboy) gave a special meaning to the national culture. “Yerba mate” (a kind of tea) is a special daily drink inherited from the gaucho’s nomadic life in the country. Uruguay projects an image that in many aspects is more European than Latin American. The rhythm of life in Montevideo is dominated by European society. Uruguay has been influenced by French culture ever since the eighteenth century. For example, the national dance of Uruguay, called “El Pericon,” is styled after the French minuet. The country has no official religion, unlike most South American countries, and has always been distinguished by its high level of literacy. The government spends more money on education than on defense. Uruguayan poetry is the richest in Latin America. There are fifteen daily newspapers with national circulation, and the country is full of avid newspaper readers.

Montevideo is almost surrounded by beautiful sandy beaches which open officially every year on December 8. There are also numerous parks and amusement parks. The city was the center of the cultural and business life of the country, and it was peaceful, with an emphasis on recreation, sports, and culture. The port of Montevideo, next to the old downtown area, played an important role in the cultural life of the city. As a close neighbor of the city of Buenos Aires, Montevideo shared the best of their theatrical repertoire and other European artists when they stopped on their way to and from Europe. All the best operas, theater and ballet companies, and even circuses, passed through Montevideo either before or after their performance in Buenos Aires. My parents always had tickets thanks to their good friend Maria Luisa Iribarne de Batlle Berres. She was a direct descendant of Basques and very active in one of Montevideo’s Basque Centers, Euskal-Erria. She was also the sister-in-law of a former Uruguayan president, Luis Batlle. She knew my family would enjoy attending all the cultural performances the country offered, and she made it easy to get tickets. I was the one who enjoyed these events most because of my age and my preference for the theater.

Soon after school started, one of my parents’ friends gave a party and I was invited. That afternoon I met a lot of children my age, 10-12 years old, in a more formal setting. We had a lot of sweets to eat, a clown to entertain, and games to play. When the party was over I was invited to go for a week to visit the “chacra” (farmhouse) of one of the girls, Graciela, and her family. I continued to go with them for weekends or during vacations if there were no conflicts with my parents’ plans.

This farm was a summer residence for the Biraben family, which became my second family. With them I learned a lot about my new country, which was so different from the one I had just left. I learned first about the surroundings and then I started to learn about their people. The farmhouse was 25 miles from the city in the middle of an extensive prairie, with roads bordered with eucalyptus trees. I learned about the simplicity of their lives based on the gaucho’s folk culture and their lives on the plains with cattle and horses. I learned about the peculiar drink, mate, sipped through a silver straw from a gourd. My friend gave me one so I could be part of the group. I liked the sweet taste of this beverage, which we never drank at home.

I also learned about their informal setting and their way of talking about everything sitting a big circle – adults and children together – listening in the background to a sentimental gaucho with his guitar singing to the stars. I was a child but I could talk to them, usually answering questions. This was a contrast to the formality and rules of the society in Europe, where I was supposed to not be involved in conversation with older people. Our main dish for supper was usually parrillada criollla, or barbecued steak, which was also new for me. They had a housekeeper, Maria, who baked delicious desserts as well.

The land of Uruguay produced all kinds of vegetables and fruits, but the main product was their vineyards. Close to the main house lived a family from Italy who cared for the fifteen-acre farm. It was a beautiful and serene place to be. I loved to go with them. I learned not only about Uruguayan rural life but also about French popular music, such as the singing of Maurice Chevalier, which they played a lot.

I started to change. My assimilation to the country was eased by my friendship with Graciela and her family, which taught me about their culture and ways of living, and they also accepted me as I was. My different culture was not an obstacle for them to accept me as a person. The conflicts that arose with my acculturation and fast assimilation to the new country came more as a consequence of the differences in my parents’ background and their Basque values, which we preserved at home, rather than the new culture I was confronting.

The school started to gain importance in my life in these days. I had a nice group of friends called “La Barra” (“The Beam”). All my friends enjoyed and were active in school events. We also studied together a lot. I was at the age when my friends were the most important thing. Since my new friends and Uruguay became very important to me, my parents were a little bit concerned because their only thought was to go back to Euskadi to continue their life as it was before the Civil War.

Life in exile is a life of denial of the present. Their lives were confined between the whimsical past and the future represented by the illusion of return. Of course these tensions affected our family life as they grew accustomed to the country where they did not choose to live. My parents were worried that my siblings and I could be absorbed by the host culture so my father did a lot to instill in us the knowledge of, and love for, our heritage. He taught us to speak, to sing, and to pray in the Basque language, and about all the mythology of this medieval culture. My mother also showed us our heritage in the best way she could, by cooking the best Basque dishes without adapting to the country’s culinary customs.

I saw my parents suffering for the Basque cause. In those days the United Nations admitted Spain under Franco and that killed all the chances of the political exiles like my parents to return to their homeland. My father became very depressed because his dreams were shattered. It was difficult for me not to feel my father’s sadness and disappointment but I could not talk to my friends about that. My friends didn’t understand the word “exile” or the word “Basque”. These two words were the center of our existence at home but I couldn’t share this part of my life with my friends. But I participated in the rest of the activities of a teenager’s life. I went to parties, movies, the beach, and school religious functions because I loved the positive feelings that they provided me to be accepted. With my parents I lived a different kind of life, a life connected completely with the Basque world and the Basque clubs like Euskal-Erria, which was very culturally and socially oriented. I participated in the VII General Conference of UNESCO, where my father was named Delegate from the Ministry of Education of Uruguay as the conference’s principal organizer.

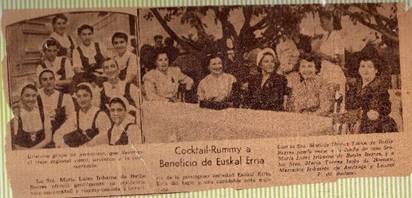

Exiles like my parents were few in Montevideo. Most of the Basques who could escape to America from Franco’s claws were in Argentine, Venezuela or Mexico. The Basques who were in Uruguay were descendants of

Basques for one or more generations who came to Uruguay at the turn of the

century, 40 years earlier. My father was one of the few who were suffering a

recently imposed exile. My mother was happy wherever he was, but he felt

passionately his frustrations and he fought to make the Basques known in Uruguay. In Euskal-Erria they celebrated the traditional festivals such as Aberri-Eguna

(Day of the Fatherland, on Easter Sunday), Saint Ignatius (July 31) and Dia del

Euskera (Day of the Basque Language, December 3). These celebrations, carried

out with contagious enthusiasm and vigor, strengthened their collective bonds

and they made a powerful and emotional impact on everyone. I would participate

by serving tables at the card games (rummy-canasta) dressed in the traditional

Basque costume, called the poxpolina. A large number of club members

participated, filling the big meeting room of Euskal-Erria. This salon had

been decorated in a rustic style reminiscent of a Basque farmhouse. In one

corner against the wall was a replica of a Basque kitchen with a fireplace used

in a typical caserio. In these farmhouses the kitchen has been the most

important room ever since ancient times. The activities of the house centered

on the life-giving fire which seemed always to be burning. Above it hung a

pot-hook from an iron chain and strings of onions and dried sweet peppers. A

rustic cotton material designed with navy blue and whit squares was used for

the tablecloth and the “borlas” or tassels (worn by cattle in the caserio).

The same cloth hung from the rustic chandeliers and windows and gave the room a

unique atmosphere. It was a very pleasant and cozy room for me. The newspaper clipping above describes one of these events. Ama is

the second from the left of the women sitting at the long table.

Exiles like my parents were few in Montevideo. Most of the Basques who could escape to America from Franco’s claws were in Argentine, Venezuela or Mexico. The Basques who were in Uruguay were descendants of

Basques for one or more generations who came to Uruguay at the turn of the

century, 40 years earlier. My father was one of the few who were suffering a

recently imposed exile. My mother was happy wherever he was, but he felt

passionately his frustrations and he fought to make the Basques known in Uruguay. In Euskal-Erria they celebrated the traditional festivals such as Aberri-Eguna

(Day of the Fatherland, on Easter Sunday), Saint Ignatius (July 31) and Dia del

Euskera (Day of the Basque Language, December 3). These celebrations, carried

out with contagious enthusiasm and vigor, strengthened their collective bonds

and they made a powerful and emotional impact on everyone. I would participate

by serving tables at the card games (rummy-canasta) dressed in the traditional

Basque costume, called the poxpolina. A large number of club members

participated, filling the big meeting room of Euskal-Erria. This salon had

been decorated in a rustic style reminiscent of a Basque farmhouse. In one

corner against the wall was a replica of a Basque kitchen with a fireplace used

in a typical caserio. In these farmhouses the kitchen has been the most

important room ever since ancient times. The activities of the house centered

on the life-giving fire which seemed always to be burning. Above it hung a

pot-hook from an iron chain and strings of onions and dried sweet peppers. A

rustic cotton material designed with navy blue and whit squares was used for

the tablecloth and the “borlas” or tassels (worn by cattle in the caserio).

The same cloth hung from the rustic chandeliers and windows and gave the room a

unique atmosphere. It was a very pleasant and cozy room for me. The newspaper clipping above describes one of these events. Ama is

the second from the left of the women sitting at the long table.

These card games collected money that was used at Christmas time to distribute to Basque elderly people living in nursing homes. The Basque club gave each of them a big basket with all kinds of foods and sweets appropriate for the season. Seeing these happy people was a very rewarding experience. I could see that with my modest contribution I had made somebody happy.

The person I most admired in Uruguay was Maria Ana Bidegaray de Janssen, a close friend of the family and the God-mother of my younger brother. A widower, she had been born in Hasparen (Laburdi) one of the French Basque provinces. She was educated at Bordeaux and moved to Uruguay with her family when still young. She married the Belgian Consul to Uruguay, Raymond Janssen. During World War I, Marianita (as she was called at home) worked very hard to help the Belgian people, for which she was decorated by the Belgian King Albert I. Now she was working with the same enthusiasm for the Basque cause. She wrote a book entitled “Cuna Vasca” (“Basque Cradle”). Her rich and cultivated personality influenced me very much. Marianita combined the virtues of serenity, wisdom, compassion, and she also had a cosmopolitan taste. She had lived in many countries and she knew how to absorb the best of each of them. My family visited her very often at her nice home in Carrasco, a resort town on the outskirts of Montevideo. I used to listen with pleasure to her stories of the Far East, China, India and the Mediterranean. I wanted very much to be just like her someday.

I tried hard to achieve an important goal in life – to succeed in my studies – with so many examples before me, but after much study I showed only average grades, with the lowest in math. I couldn’t convince my parents of my seriousness in studying medicine. I felt my parents’ pressure to pursue a secretarial course, with short-hand, typing and English. That course was offered at the British School very near our home. I was stubborn and declined their offer. I wanted at least to try something more challenging. If I could only demonstrate that I was serious and I was eager to work. But I didn’t know why I had so little to show for all my effort. Nevertheless I was inclined to work at my own pace and on my own terms.

During Carnival in Uruguay we all went to see the “tablado” or parade floats near our home, near the beach of Pocitos, from where the great parades started featuring the King “Momo”. Everyone wore costumes and they threw confetti at the crowds. The orchestras were loud, playing happy music, or folk music like “La Comparsita”. There was a week with an unfolding of color, rhythm and music. The beginning of Lent was Ash Wednesday when all the faithful are exhorted to kneel before the priest and receive on their forehead a sign of the cross with ashes. We were not allowed during this season to attend parties or dances. The Lenten fast led up to Holy Week. Holy Thursday the churches were in near darkness to symbolize the desertion of Christ by his disciples. The solemn mood continued through Good Friday when the church stood desolate and bare, its altar draped in black, its statues covered in purple.

Easter Sunday was both a religious and a patriotic celebration that was accompanied by our best food and best dresses. After a Mass we all went to the Euskal-Erria the rest of the day to celebrate “Aberrieguna”.

Ships arriving in Montevideo from Europe brought us food from the homeland, such as “turron” (a nougat paste made from almonds, pine kernels, nuts and honey) mazapan (marzipan), and gifts from my aunts and other family members. My mother always cooked something very special for Christmas night, but the desserts were supreme, such as “compota” (fruit compote) or “Tocino de cielo” (heavenly pudding). The table would be beautifully decorated with our best linen tablecloth. We ate and sang songs my father taught us from his childhood. The only sad note was the large framed color picture of the absent daughter and sister that was placed in a chair at the table as mute testimony to the fact that she was missed.

Christmas season was summer in Montevideo. My mother enjoyed very much making the Nativity scene decoration. She used paper mache that was especially painted to resemble rocks, stones and hills for the background. She used mirrors to imitate the rivers and put small houses all around and the main figures under the manger. The scene was covered by fresh moss which filled the room with a special Christmas fragrance for the entire season. The three Wise Men traveling to Bethlehem were moved every day by one of my siblings. On January 6 we celebrated the “Reyes Magos”. The Wise Men arrived at the manger offering gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and we children received small gifts in our polished shoes. The main gifts were always hidden in some other place.

We celebrated our birthdays with almost the same enthusiasm as Christmas. Early in the morning the birthday person stayed in bed until he or she was awakened by the rest of the family. They came in with improvised drums (pots and pans) singing “Zorionak Zure,” the Basque version of “Happy Birthday”. A lot of small gifts were given to be opened later in the day. A very good friend of the family always came to these parties. He was very well received because he brought old movies of Charles Chaplin that we all enjoyed, especially my father.

Uruguay gave me what I needed most in those

years, and I was molded by the country’s sweet, cultural and spiritual life

with hope and promises. I loved Uruguayan life. This photo was taken at a

farewell party given for the Amezagas by the family of one of Arantza’s

friends, Martita Pizza Nogueira in Carrasco. Xabier is on the left, behind him

is Martita’s father, Bingen on the right, Arantza is second from the right, Martita,

Ama and Mirentxu are in the middle.

Uruguay gave me what I needed most in those

years, and I was molded by the country’s sweet, cultural and spiritual life

with hope and promises. I loved Uruguayan life. This photo was taken at a

farewell party given for the Amezagas by the family of one of Arantza’s

friends, Martita Pizza Nogueira in Carrasco. Xabier is on the left, behind him

is Martita’s father, Bingen on the right, Arantza is second from the right, Martita,

Ama and Mirentxu are in the middle.