|

AMEZAGA

EGUBERRIAK 12-2008 ALZUZA PAMPLONA

HOMENAJE A PELLO

IRUJO

|

|

|

| Antecedentes

Travesia

The Lives of Vicente Amezaga y Mercedes Iribarren |

|

France: 1938-1942

Until the end of March 1937

the Spanish Civil War was far away from the Basque Country, or at least from

Vizcaya. The Basques felt safe

because the Cantabrian Mountains separated them from the rest of Spain. They did not know, however, about the

help that the Nationalists had received from Hitler and Mussolini with troops

and the Condor Legion bombers.

Franco started his

offensive against Euskadi with fury and one of the first events was the bombing

of Guernica. Guernica was one of many bombed towns in

the Spanish Civil War, but Pablo Picasso’s interpretation of the attack

through his famous painting turned it into one of the best known events of the

century. His painting converted the

ashes of Guernica

into a symbol of Nazi terror from the air, and the whole event became the most

famous episode of the war.

On April 26, 1937, my

parents were in Mundaca, on the left bank of the Guernica

River about seven miles north of Guernica. As Director of Education for the Basque

Government, my father was inaugurating a school in Mundaca that morning. My parents were having lunch with local

authorities when they saw continuous flights of the big silver bombers of the

Condor Legion flying out over the Bay of Biscay to wheel and turn upriver

toward Guernica. At first they thought it was only a

reconnaissance operation but the continuous flights sacred the entire

population of this small resort area and they took refuge for some time until

they could leave the town. At 9:00

pm the radio broadcast a message from the pastor of the Santa

Maria Church of Guernica who in a

pathetic voice told the terrible news.

The most painful thing

about this attack is that it was not done out of rage but out of

indifference. The Germans were only

practicing how to conduct such attacks in the next, bigger war. But when they bombed the town they were

ignorant of the symbolism of the village.

Guernica is the historical

capital of Vizcaya, locatd about 15 miles east of Bilbao.

The village was founded by Don Tello, Count of Vizcaya, half brother of

Pedro I of Castille, on April 28, 1366.

The town is the site of the famous symbolic oak tree and the Casa de Juntas, the

representative assembly of Vizcaya.

Representatives of all the villages in Vizcaya had a seat and a vote in

the assembly, and their early meetings were held beneath the tree of Guernica. The first recorded meeting of the

assembly was in 870 AD. It was here

that the kings of Castille would pledge to respect the local privileges of

Vizcaya and ever since then the tree has been the symbol of their

independence. The assembly still

possesses the “Old Privileges,” (known as fueros), the “Historical Archive,” and

the original manuscripts of the most famous Basque poet and composer,

Iparraguirre (1820-1881), the composer of the stirring anthem “Gernikako

Arbola” (“The Tree of Guernica”).

Monday, April 26, 1937, was market day in Guernica,

the ancient and sacred town of Vizcayans,

and of Basques generally. That day,

the town’s population was swollen beyond its normal size of about 5,000

by the farmers who had come to sell their produce in the market and by the

hundreds of refugees who streamed through the town toward Bilbao in flight away from the war front,

barely 15 miles to the east.

Despite its total lack of military significance, the town had prepared

for an aerial assault after the bombing of nearby Durango the preceding month.

The attack began at 4:30 pm, carried out by the German

Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion.

The attackers used explosive munitions at first, then switched to

incendiary bombs in a fourth wave about 6:30 pm. Fighters strafed the fleeing population

with machine gun fire near the end of the assault. Only years later was it learned that the

Luftwaffe used attacks such as these to test their weapons and tactics to

perfect their use of strategic bombing for the impending war. Virtually the entire center of the town

was destroyed. Not a single

building escaped harm except – as if by miracle – the Casa de

Juntas and the sacred oak tree.

Casualties reached 1,654 killed and 889 wounded. Vicente Amezaga and Mercedes Iribarren

were attending the dedication of a new Basque school at a nearby town that

afternoon when they saw the planes circling overhead as they gathered in

formation for the assault. The

violence of modern war was a part of the life of the Amezagas even before they

could begin to form a family. It is

fitting, therefore, to begin the story of the Amezaga family with the seal of

the City of Paris,

where it began: Fluctuat nec mergitur,

“tossed by the waves, she does not sink.”

The attack began at 4:30 pm, carried out by the German

Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion.

The attackers used explosive munitions at first, then switched to

incendiary bombs in a fourth wave about 6:30 pm. Fighters strafed the fleeing population

with machine gun fire near the end of the assault. Only years later was it learned that the

Luftwaffe used attacks such as these to test their weapons and tactics to

perfect their use of strategic bombing for the impending war. Virtually the entire center of the town

was destroyed. Not a single

building escaped harm except – as if by miracle – the Casa de

Juntas and the sacred oak tree.

Casualties reached 1,654 killed and 889 wounded. Vicente Amezaga and Mercedes Iribarren

were attending the dedication of a new Basque school at a nearby town that

afternoon when they saw the planes circling overhead as they gathered in

formation for the assault. The

violence of modern war was a part of the life of the Amezagas even before they

could begin to form a family. It is

fitting, therefore, to begin the story of the Amezaga family with the seal of

the City of Paris,

where it began: Fluctuat nec mergitur,

“tossed by the waves, she does not sink.”

May 7 fell on a Saturday in 1938. The Amezagas’ first child entered

the world as Europe was passing through what

came to be called “the May crisis.” Adolf Hitler, fresh from his coup in Austria,

now threatened neighboring Czechoslovakia

over the rights of German-speaking Czechs living in the western end of the

nation, known as Sudetenland. Czechoslovakia

was determined to resist the threat from its much more powerful adversary, France had a treaty obligation to defend Czech

independence, and Britain

was allied with France to

attempt to restrain Hitler’s ambitions in Eastern

Europe. Europe seemed headed for a repeat of the 1914 chain of

miscalculations that began the Great War.

As it turned out, the threat receded. The French government flinched and

sought an alternative way out, Britain

breathed a sigh of relief that their IOU had not been called in, and Hitler

realized that he might be able to get what he wanted in Czechoslovakia without a war. With the advantage of hindsight we now

know that World War II had merely been postponed 15 months but at the time the

sense of relief was palpable.

Now my parents were in Paris, together. “Paris is a party of life,”

Ernest Hemingway said a city that has been praised in story and song. Street painters with long beards made

the Paris of

their dreams on their canvas. No

other city in the world had as many painters as Paris.

When my father joined my mother in Paris

after long months of separation, she was eight months pregnant and living with

her sister Tia Juli in a small apartment.

To compensate for the four months of separation and hunger they had been

through, they celebrated by dining at the “Thirteen Francs”

Restaurant on the Champs-Elysees where for just thirteen francs they could get

half a lobster and ice cream for desert.

After my birth, they moved to a larger apartment, and Tia Juli moved

with them. She opened a fashion

design and sewing shop in the same apartment, which was quite large, and she

and my mother enjoyed going to the fashionable events of the city, such as

weddings, to see the latest styles.

Mercedes’s first pregnancy almost ended tragically. The baby was turned incorrectly as birth

neared and the doctor had to resort to the extensive massages and use of

forceps to turn her head correctly.

At one point, he left the delivery room to tell Vicente that he thought

they could save his wife but the baby would probably not survive. Mirentxu of course had other plans, and

emerged kicking and healthy although her face was marked by the forceps for

days thereafter.

The morning of May 7 Paris’s main avenues

were all decorated. The city was

getting ready to celebrate their national heroine and patron saint of France,

St. Jeanne D’Arc, called the Maid of Orleans, who united the nation at a

critical hour and decisively turned the Hundred Years’ War in

France’s favor.

Looking out on to the broad

avenues of the city through the window in a small waiting room of the clinic of

Vincennes was a man of medium frame, blond hair, deep blue eyes hiding under

dark-framed glasses.

Absent-mindedly he observed the people outside as he waited for so many

hours anxiously. His name was Vicente. He was my father.

Many hours earlier Dr.

Lamaze, my mother’s obstetrician, told him that his wife would be okay

but they couldn’t assure him the same for the baby. The child was in danger. Vicente was thinking how ironic that his

first child perhaps would never see the light of day in the Ville lumiere, the city of

lights as they called Paris.

The “Dr. Lamaze” referred to above was the soon-to-be

world famous Dr. Fernand Lamaze, the founder of the Lamaze method for natural

childbirth. Lamaze was born in 1891

and died in 1957. In 1951 he

introduced his method of childbirth in France

by incorporating techniques he observed in Russia. This method included childbirth

education classes, relaxation, breathing techniques, emotional support from the

father, and leaving the baby and mother together 24 hours per day from the

beginning. The method became

extremely popular around the world and especially in the United States. In 1938 Lamaze had not yet discovered

painless childbirth but he was the most famous obstetrician in Paris

and women came from all of France

to be attended by him. It is not

speculation to suppose that in the hands of a less skilled obstetrician,

Mirentxu’s birth would have ended tragically.

It was almost dark. He was getting impatient looking again

and again at his watch that hung from the silver chain. It was almost 9:00. He felt more of a stranger in that city

to which he had come only a month earlier.

Paris is

the city of the exile. Chopin went

there to compose, Picasso to paint, and James Joyce to write Ulysses. He too came to exile escaping the Spanish

Civil War. How much it hurt to

think of what he left behind.

Suddenly his thoughts were interrupted by the voice of Dr. Lamaze who

announced with joy “We have saved the baby. It’s a girl.”

My father (from now on,

Aita) quickly left the almost dark waiting room to join his wife and baby. His wife (from now on, Ama) was tired

but pretty as ever and radiant.

Next to her was a pink crib with their new daughter. At that precious moment they were both

very happy looking proudly at the new member of the family, and the shadow of

the war was forgotten for a moment.

A few days later we left

the Vincennes Clinique to go to our house

located at Rue Bonaparte #18, 6th Arrondisement, on the Left Bank of

the Seine. They passed the narrow streets filled

with antique shops. They passed the

Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts, established in 1816, whose students could be

seen painting and sketching on the nearby wharves and bridges. My parents looked at the students more

attentively as if they wanted to tell them of their new role as proud parents

of a French child. Now they felt

less like immigrants.

Two weeks after her birth, Aita y Ama had their first child baptized

in the oldest church in Paris,

St-Germain-des-Pres, which was located just a short walk from their apartment

on Rue Bonaparte. The church was

built to house a relic of the True Cross brought from Spain in 542 A.D. The church began as a Benedictine abbey

founded by Childebert, the son of Clovis. The Normans all but destroyed the abbey at least

four times, and very little remains of the original structure. The church was enlarged and

reconsecrated by Pope Alexander III in 1163. The abbey was completely destroyed

during the French Revolution but the church was spared.

Two weeks after her birth, Aita y Ama had their first child baptized

in the oldest church in Paris,

St-Germain-des-Pres, which was located just a short walk from their apartment

on Rue Bonaparte. The church was

built to house a relic of the True Cross brought from Spain in 542 A.D. The church began as a Benedictine abbey

founded by Childebert, the son of Clovis. The Normans all but destroyed the abbey at least

four times, and very little remains of the original structure. The church was enlarged and

reconsecrated by Pope Alexander III in 1163. The abbey was completely destroyed

during the French Revolution but the church was spared.

Mirentxu, the equivalent in

the Basque language of Marie, was the name I was called at home. From the time I learned how to walk I

was waiting happily for my father at the front door with his slippers. My father adored me. He enjoyed feeding me, and he imposed

that chore on himself every day. He

wrote a poem dedicated to me that described these moments.

Mirentxu, the equivalent in

the Basque language of Marie, was the name I was called at home. From the time I learned how to walk I

was waiting happily for my father at the front door with his slippers. My father adored me. He enjoyed feeding me, and he imposed

that chore on himself every day. He

wrote a poem dedicated to me that described these moments.

Shortly after Mirentxu was born, the family moved to a larger

apartment on Rue Goethe #1, near Marceau

Avenue, in the 16th

Arrondissement. The

photo on the right, taken by Mirentxu during her trip to Paris in 1995, shows their apartment

building. Their apartment was the

first from the street level with a balcony (on the third floor of the

building).

My parents loved the

neighborhood of the new apartment.

They loved the great boulevards and the little side streets lined with

old houses, cafes large and small, cheap and expensive restaurants, and they

were captivated by the quays and bridges on the Seine

and the monuments that combined the ancient and the modern.

Tia Juli, who was my

godmother, had a fashion design shop in Paris, and she lived with us. She had been like a second mother to

Ama, and now they were best friends.

Juli was an energetic and creative person, talented in fashion design,

who admired the beauty in everything.

Above all she had an extraordinary ability to convert any kind of cloth

into a beautiful garment. In her

high fashion shop she saw people from the most glamorous social position to the

middle class. On Sundays she often

went to the Eglise de la Madeleine to see the weddings. By the ring of the church chimes she

knew the level of the wedding. Juli

was interested because the dresses were designed by the best shops in Paris. My mother accompanied her many times.

Ama also loved to go to the

open market two blocks from our house once a week. There she found boxes of oranges,

apples, lemons, grapes, strawberries, pears, and cantaloupes, as well as

flowers piled high in pyramids.

What was amazing, she used to say, was the variety of cheeses they

had. The French said they have a

different kind of cheese for every day of the year. Next to the market was a bakery with the

wonderful aroma of fresh bread.

People carried the long baguettes under their arms.  There was also nearby a small fish market

where the smells of fresh fish competed with the garden perfume of lettuce,

celery, leeks and radishes.

There was also nearby a small fish market

where the smells of fresh fish competed with the garden perfume of lettuce,

celery, leeks and radishes.

The stores and markets

attracted swarms of people trying to decide what to buy as they listened to the

continuous chorus of the sellers as they yelled the different prices. My mother enjoyed shopping for food, and

she cooked as happily as she shopped.

Now that they lived on the Right Bank, they had access to the more

typical part of Paris, such as the Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triomphe, Place de la

Concorde, Palais de Chaillot, the Champs Elysees, and the Jardin des

Tuilleries, where they loved to take me in the stroller.

One reason for moving to this new apartment was that it was just a

short walk from the location of the Basque Government in Exile in Paris, #11

Rue Marceau (see photo). This

office, officially referred to as the “Basque Delegation”, was

opened when the Civil War broke out in 1936, and coordinated the actions of the

Basque Government between 1937 and 1940.

Aita worked there as secretary to the Basque Minister of Justice,

Jesus Maria Leizaola. In addition,

he and Mercedes traveled several times to London

to inspect the conditions of the colonies established there for the Basque

refugee children. When they went to

London, they

left Mirentxu for several months with Tia Juli and a nurse. It

was the first time since they were married that they were going to be alone and

they needed that, because what lay ahead of them would be a painful experience

for them both. For the most

part, though, the Amezaga family carried on a relatively normal life

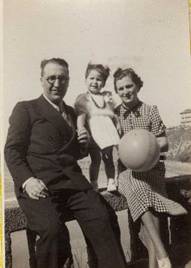

considering the tragedy and violence they had seen. These photos show Ama and Mirentxu on

the balcony of their apartment in Paris (Ama is

knitting for their second baby) and Aita and Mirentxu during a family outing to

the Tuilleries Gardens near their home.

Aita worked there as secretary to the Basque Minister of Justice,

Jesus Maria Leizaola. In addition,

he and Mercedes traveled several times to London

to inspect the conditions of the colonies established there for the Basque

refugee children. When they went to

London, they

left Mirentxu for several months with Tia Juli and a nurse. It

was the first time since they were married that they were going to be alone and

they needed that, because what lay ahead of them would be a painful experience

for them both. For the most

part, though, the Amezaga family carried on a relatively normal life

considering the tragedy and violence they had seen. These photos show Ama and Mirentxu on

the balcony of their apartment in Paris (Ama is

knitting for their second baby) and Aita and Mirentxu during a family outing to

the Tuilleries Gardens near their home.

By January 1939, when Barcelona fell

to Franco and the Civil War ended in the defeat of the Second Republic,

Ama was pregnant with her second child.

With the prospect of an impending general war across Europe and an

extended exile facing them, many Basques began to relocate to safer locales,

especially in the Western Hemisphere. A wealthy Basque immigrant to the Philippines

named Manuel Inchausti created the International League of Friends of the

Basques, an organization that raised large sums of money to assist in these

relocations. The Basque Government

also provided aid as did the Emigration Service of Spanish Republicans, funded

by the Spanish, Basque and Catalan governments. The Basque Government sent

numerous delegations abroad – to the United

States, Mexico,

Venezuela, Chile, Uruguay

and Argentina

– to prepare the way for those desiring to emigrate.

After Barcelona fell to Franco in March 1939, the

Spanish Civil War was over. Franco

was proclaimed caudillo for life and given absolute authority. Meanwhile Paris never looked better. In July of that year they celebrated the

150th anniversary of their glorious revolution with patriotic and

social parties and celebrations at Versailles

almost every evening. Life in France

seemed better after a decade of depression. The traditional parade and air force

display on the Champs-Elysees on July 14, Bastille Day, were very impressive

and gave the French people the confidence that they were powerful enough to win

against Hitler.

In the spring and summer of 1939 Paris

lived through a period of false optimism, thinking that perhaps Hitler had

changed his mind about taking Europe into

another war. But in late summer,

tensions rose again and France

put the Maginot Line on alert and called up two million troops. Mercedes’ doctor called to say

that he had been called to military service and she should look for another

physician to attend her second delivery.

Aita and Ama decided to move to Biarritz,

where the Basque Government had established a splendid hospital, called La

Roseraie, which attended the medical needs of the thousands of Basque refugees

in France. After much effort, Aita was able to

purchase tickets for the train from Paris to Biarritz, but on the day

they were scheduled to leave Ama went into labor. Germany

had the previous day invaded Poland,

and France and Britain had declared war on Germany, so Paris was in chaos. Hundreds of thousands of Paris residents attempted

to flee the city and the roads and trains were all jammed. Aita frantically tried to get a taxi to

stop to take Ama to the hospital but to no avail. Fortunately, the Basque Delegation was

able to send a car for them and they arrived at the hospital with only an hour

to spare before Mirentxu’s sister, Begona, was born. She

was baptized Miren Begona de la Paz (for Peace). I was only 16 months old. Since the hospital was closed the next

day, the family had to return to their Paris

apartment to await the next developments in the war. But no attacks came and the so-called

“false war” lulled the French once again into thinking that war

would not come.

The fall of Paris was sad and dark,

under the threat of German attack.

With no actual bombardment people started coming back from the country. In the dark capital the night life

continued the same even though the public places and restaurants were closed at

ten at night. In May 1940 German

forces invaded the Netherlands,

Belgium and France. The main weight of their armored forces

struck at a weakly defended position in the French line and on May 15 they

broke through and raced to the Channel coast. On June 9 the Germans attacked across

the Somme River and pushed on to the south. As their armored columns spread across

the country, the roads became clogged with fleeing refugees and the French army

disintegrated. Two-thirds of French

territory was occupied by German forces.

June 14, 1940, in the

evening Paris

saw Hitler’s jubilant troops enter the city without firing a shot. The Germans hoisted the swastika on the Eiffel Tower

and the same day the French government flew to Bordeaux

in southwestern France. The Basque government was now leaderless

because its president was trapped in occupied Belgium,

but the members of the government decided to move their seat to Bordeaux. My father was told to find a safe place

there. He left Paris

several days before the Germans occupied the port of Bordeaux. Five days later the Germans bombarded Bordeaux for the first

time. The situation in Bordeaux was very

precarious. The first night there

was a heavy bombardment near where they were staying. The trains out of Bordeaux

were filled. Aita, Ama and Begona

waited for hours before they could find train space for the three of them, but

they had to leave all their baggage at the station because there was not enough

space.

In May 1940 the unsteady peace ended and Hitler’s forces

invaded Holland, Belgium

and Luxembourg. Just days before, the Basque President,

Aguirre, and his family had gone to Belgium on holiday, and they were

caught on the German side of the war front. The president went into hiding, assumed

a false identity, and managed to evade capture for several years while he

traveled into Germany,

eventually to escape with his family via Sweden to Brazil.0

Minister Leizaola now assumed authority of the Basque Government and

sent Aita to Bordeaux

to find a suitable site for the government’s offices. The French Government was already

relocating its offices there. Aita,

Ama and Begona went to Bordeaux and sent

Mirentxu with Tia Juli farther south, to Biarritz.

On June 14, Paris

was handed over to the Germans without a shot fired in its defense. On June 16, Marshall Petain assumed

control of the French Government, sued for peace, and established itself in the

town of Vichy. From there, the French exercised control

over the southern half of France

while the Germans occupied the northern half. Meanwhile, seeing that it would be

futile to stay in Bordeaux, and unable to return

to their Paris apartment to gather their

belongings, Aita and Ama decided to go with Begona on to Biarritz to rejoin Mirentxu and Tia

Juli. Between 1940 and 1944, German

occupation authorities confiscated over 38,000 apartments in Paris, along with furnishings. Among these was the Amezagas’

apartment, which was lost to them forever.

The trip from Bordeaux to Biarritz

took three hours. Biarritz is one of the most famous seaside

resorts in the world. In

southwestern France

it is located on the fringe of the Basque country. It has broad sandy beaches perfect for

swimming and sun bathing. Cliff

walks forming a grand promenade are one of its most enduring attractions. The town was once a simple fishing and

whaling village that became an elegant resort in the middle of the nineteenth

century when the Emperor Napoleon III, the Empress Eugenie and other members of

European royalty were frequent visitors.

Now the beaches were empty and the streets were full of German soldiers

who inspired terror.

Aita knew at once that his

life was in danger in Biarritz. He could have been deported to Spain

where he would have been killed.

The dreadful moment of leaving came again. This time was worse because they had two

small children. So he decided to sail

to England

alone. But after waiting in vain

with other people to board a ship to London he

decided to go to Marseille where he might find a ship to England more easily. But it was still dangerous to move with

the entire family, so Ama, Tia Juli, Begona and me remained in Biarritz, where this photo of the two girls

on the beach was taken.  Ama had lost all their possessions. She cried alone at night. The only thing left to do now was to

look after her two baby daughters and to wait for news from her husband. When he got to Marseilles, Aita found it

extremely difficult to arrange passage, but he soon learned that a ship might

be available soon. Although the

ship would accept only male passengers, Aita still wanted Ama to join him in Marseilles until the ship

left.

Ama had lost all their possessions. She cried alone at night. The only thing left to do now was to

look after her two baby daughters and to wait for news from her husband. When he got to Marseilles, Aita found it

extremely difficult to arrange passage, but he soon learned that a ship might

be available soon. Although the

ship would accept only male passengers, Aita still wanted Ama to join him in Marseilles until the ship

left.

Communications between Aita and Ama were next to impossible during

these days. Telephone

communications had been cut and mail was intercepted and read by the Vichy

French government. Aita found a

Basque who served as a courier carrying secret messages between Marseilles and Biarritz,

and he managed to send this cryptic message to Ama: “Leave everything and

come.” Although Ama’s maternal instincts told her to stay with her

daughters, she felt that Aita needed her more at that moment. Encouraged by Tia Juli, she left several days later, after

lunch. We were taking a nap. She looked at us (she told me later) for

a long time and gave us a tender kiss full of love, tears and pain. She was crying as she had a fear of what

was going to occur later. And she

left to go to the train station. Her plan was to return to Biarritz in a matter of

weeks. This photo was the last

taken in Biarritz

before her departure.

Aita and Ama waited in Marseilles

until word came of a ship available to take refugees to American ports, and was

also accepting women and children as well.

They sent an urgent message to Juli that she should bring the girls to Marseilles and all five of them could leave France

together. Juli replied that she was

going to return to Las Arenas, to be with her father who was ill and she would

take the girls with her. She said

that the journey on the ship was dangerous and the girls would be safe and well

cared for with their grandfather and aunts and uncle. Aita and Ama should leave by themselves

and the family could be reunited in America

or, in the best of cases, in Spain

soon.

Aita and Ama waited in Marseilles

until word came of a ship available to take refugees to American ports, and was

also accepting women and children as well.

They sent an urgent message to Juli that she should bring the girls to Marseilles and all five of them could leave France

together. Juli replied that she was

going to return to Las Arenas, to be with her father who was ill and she would

take the girls with her. She said

that the journey on the ship was dangerous and the girls would be safe and well

cared for with their grandfather and aunts and uncle. Aita and Ama should leave by themselves

and the family could be reunited in America

or, in the best of cases, in Spain

soon.

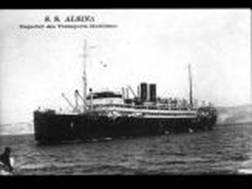

The courier on whom Aita

relied for communication was caught by the Germans and executed, leaving

everyone in the dark about what the others were doing. Faced with this most anguishing

decision, Aita and Ama arranged passage on the ship, the Alsina, and on January 15, 1941, they departed Marseilles

en route to Buenos Aires, Rio

de Janeiro and Montevideo. They would not see Mirentxu again until

1948 and Begona was never reunited with the entire family. Aita did not see her until he was near

death in Caracas

many years later. Although Mirentxu

did eventually rejoin her parents, the fracturing of the family in this way

left scars that healed only slowly over many years.

I was 28 months old and my

sister only a year, both of us too young to be separated from our mother. That painful decision brought sadness to

our hearts for the rest of our lives.

Several months later they embarked for America without us. Ama’s sister Juli didn’t

want to go to Marseilles and deliver us to our

parents as my mother begged her to do and my mother couldn’t go back to Biarritz.

Before they left Marseilles, my mother saw

a street painter and asked him to paint a picture of her children. She gave him to copy the picture of the

two girls on the beach which is on the preceding page. The painter felt her pain and he

reproduced a large colorful painting that she held against her heart. That painting was always in a place of

honor in our home for the rest of their lives.

Before they left Marseilles, my mother saw

a street painter and asked him to paint a picture of her children. She gave him to copy the picture of the

two girls on the beach which is on the preceding page. The painter felt her pain and he

reproduced a large colorful painting that she held against her heart. That painting was always in a place of

honor in our home for the rest of their lives.

When the Alsina weighed

anchor in Marseilles,

it carried 700 passengers, including about 300 Jews, 180 Basques, 38 of them

children from 1 month to 14 years of age.

When they got to Dakar in what is today Senegal, the

captain informed the passengers that he could not continue the trip. As the ship was of French registry, the

British Royal Navy would not let it leave Africa for ports in the Western Hemisphere.

The only options open to them were all bad: remain on the ship in port

indefinitely, return to France, transfer to a Spanish ship, or try to leave

French West Africa over land to some neutral country. They chose the least bad option: remain

in port indefinitely. Food was

severely rationed, diseases spread through the ship, the crew threatened to

mutiny, and Aita and Ama began to think that they had been right to leave the

girls in Europe. Finally, after nearly five months, the

ship’s owners decided to return the ship to Casablanca, disembark all passengers, and

refund most of their passage money.

They reached Casablanca

on June 10, 1941.

In Casablanca, the ship’s

passengers were divided into three groups; two groups (including Aita and Ama)

were sent to concentration camps outside Casablanca

and the third group was returned on the ship to Dakar.

The Vichy French government refused them permission to travel to the Americas

because of the danger posed by both German and British war vessels. Conditions in the camp were

horrendous. Food was scarce,

hygiene was difficult, the heat was unbearable, and disease was everywhere. Finally, under diplomatic pressure

from a number of Latin American governments, especially Argentina, France relented and granted

permission for the trip to continue.

By this point, the Alsina had

been replaced by a ship registered in neutral Portugal, the Quanza.

Compared with what they had just been through, the rest of the trip

was fairly uneventful, even if long.

After stopping for varying periods in Bermuda and Vera Cruz, Mexico, the Quanza

docked in Havana

and the passengers were all put ashore.

There they waited for three months for the arrival of a third ship, the Rio de la Plata, from Argentina, which carried them on to their final

destination: Buenos Aires. They arrived on April 15, 1942, 15

months after leaving Marseilles. They sold the only thing of value they

had left, Mercedes’ earrings, and with this tiny sum they began to create

a home in a new land.

Meanwhile Mirentxu and Begona remained in the Basque Country staying

with their uncle, aunts and grandparents.

Here are the two girls with their Tio Ino Iribarren, Ama’s

brother, (in San Sebastian) about 1941, shortly

after crossing the border into Spain,

and their Abuelo Iribarren, Ama’s father (in Las Arenas) about 1943.

Meanwhile Mirentxu and Begona remained in the Basque Country staying

with their uncle, aunts and grandparents.

Here are the two girls with their Tio Ino Iribarren, Ama’s

brother, (in San Sebastian) about 1941, shortly

after crossing the border into Spain,

and their Abuelo Iribarren, Ama’s father (in Las Arenas) about 1943.

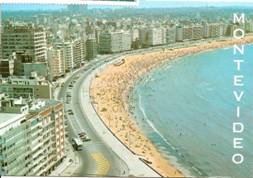

Argentina and Uruguay:

1942-1955

Uruguay

is often referred to as the Switzerland of Latin America but actually New Zealand is

a more apt comparison. Like New Zealand, Uruguay is a small country with

large neighbors, with whom they compete with vigor. Its economy depends on the export of

livestock, especially sheep. Its

population is very nearly homogeneous and European in origin, the indigenous

peoples having been pursued very nearly to extinction. And it very largely has been outside the

mainstream of world affairs for most of its existence, and certainly in the

past century or so.

In 1516, the Spanish explorer Juan Diaz de Solis led the first European

expedition to the broad estuary formed by the union of several great rivers to

flow into the Atlantic Ocean. The estuary came to be called the Rio de la Plata but neither was it a river nor did it

lead to silver as the name implied.

None of this mattered to Diaz de Solis as he and virtually his entire

expedition were wiped out by the indigenous people, known as the Charrua, who

fought ferociously against European intrusion and paid for their resistance by

being destroyed. For more than a century no European came back to the Rio de la Plata to stay. The Spanish eventually established a

colony near the origin of the estuary on the western side some distance from

the ocean, a colony that grew to become one of the world’s great cities, Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina. In the 1680s, the Portuguese sought to

counter Spanish control by founding their own colony on the eastern side across

from Buenos Aires. In a counter-move to block the

Portuguese, the Spanish decided to establish a foothold on the eastern side at

the point where the estuary empties into the Atlantic. On Christmas Eve, 1726, the Spanish

governor of Buenos Aires, Bruno Mauricio de

Zabala, founded Montevideo.

By the beginning of the twentieth century the warring factions had

resolved most of their principal grievances and began to settle down into the

Uruguayan version of two-party electoral politics. The “Whites”

(“Blancos”) were the conservative party representing the largely

rural population and the Church; the “Reds” (“Colorados”) were a

more progressive party that promoted a program of advanced social

legislation. During the presidency

of Jose Batlle y Ordonez (1911-1915), the Colorados

enacted an extensive set of social laws and programs that earned for Uruguay

the reputation of being the most progressive of all Latin American

countries.

By the beginning of the twentieth century the warring factions had

resolved most of their principal grievances and began to settle down into the

Uruguayan version of two-party electoral politics. The “Whites”

(“Blancos”) were the conservative party representing the largely

rural population and the Church; the “Reds” (“Colorados”) were a

more progressive party that promoted a program of advanced social

legislation. During the presidency

of Jose Batlle y Ordonez (1911-1915), the Colorados

enacted an extensive set of social laws and programs that earned for Uruguay

the reputation of being the most progressive of all Latin American

countries.

Throughout these decades of national development, several important

characteristics of Uruguay

determined the special nature of its capital city, Montevideo. First, the country’s economy was

based largely on livestock husbandry (cattle and sheep) and the sale abroad of

the principal products of the range: hides and wool to begin, meat after the

advent of refrigerated steamship service to Europe

in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. Such an economy could support a large

and sophisticated capital city largely devoid of heavy industry or

manufacturing. Likewise the

extractive industries like coal and oil were absent from Uruguay. Second, the colonists had virtually

wiped out the country’s indigenous population and their place was taken

by waves of European immigrants, primarily British and Italian, from the 1880s

to World War I. As a result, Montevideo, with a population of about one million by

1947, was one of the most European of all Western

Hemisphere cities.

Moreover, its location on a beautiful beach with a mild climate

year-round gave the city the flavor of a tourist resort.

Add in the progressive

nature of the Uruguayan regime in the 1940s and you begin to understand why Montevideo offered such a

warm welcome to the Basques and other Europeans fleeing the violence of civil

war and World War II. And you can

also understand why the Amezaga family would feel at home there, or at least as

much at home as people living in exile can ever feel anyplace but their own

homeland.

The attack began at 4:30 pm, carried out by the German

Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion.

The attackers used explosive munitions at first, then switched to

incendiary bombs in a fourth wave about 6:30 pm. Fighters strafed the fleeing population

with machine gun fire near the end of the assault. Only years later was it learned that the

Luftwaffe used attacks such as these to test their weapons and tactics to

perfect their use of strategic bombing for the impending war. Virtually the entire center of the town

was destroyed. Not a single

building escaped harm except – as if by miracle – the Casa de

Juntas and the sacred oak tree.

Casualties reached 1,654 killed and 889 wounded. Vicente Amezaga and Mercedes Iribarren

were attending the dedication of a new Basque school at a nearby town that

afternoon when they saw the planes circling overhead as they gathered in

formation for the assault. The

violence of modern war was a part of the life of the Amezagas even before they

could begin to form a family. It is

fitting, therefore, to begin the story of the Amezaga family with the seal of

the City of

The attack began at 4:30 pm, carried out by the German

Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion.

The attackers used explosive munitions at first, then switched to

incendiary bombs in a fourth wave about 6:30 pm. Fighters strafed the fleeing population

with machine gun fire near the end of the assault. Only years later was it learned that the

Luftwaffe used attacks such as these to test their weapons and tactics to

perfect their use of strategic bombing for the impending war. Virtually the entire center of the town

was destroyed. Not a single

building escaped harm except – as if by miracle – the Casa de

Juntas and the sacred oak tree.

Casualties reached 1,654 killed and 889 wounded. Vicente Amezaga and Mercedes Iribarren

were attending the dedication of a new Basque school at a nearby town that

afternoon when they saw the planes circling overhead as they gathered in

formation for the assault. The

violence of modern war was a part of the life of the Amezagas even before they

could begin to form a family. It is

fitting, therefore, to begin the story of the Amezaga family with the seal of

the City of  Two weeks after her birth, Aita y Ama had their first child baptized

in the oldest church in

Two weeks after her birth, Aita y Ama had their first child baptized

in the oldest church in  Mirentxu, the equivalent in

the Basque language of Marie, was the name I was called at home. From the time I learned how to walk I

was waiting happily for my father at the front door with his slippers. My father adored me. He enjoyed feeding me, and he imposed

that chore on himself every day. He

wrote a poem dedicated to me that described these moments.

Mirentxu, the equivalent in

the Basque language of Marie, was the name I was called at home. From the time I learned how to walk I

was waiting happily for my father at the front door with his slippers. My father adored me. He enjoyed feeding me, and he imposed

that chore on himself every day. He

wrote a poem dedicated to me that described these moments. There was also nearby a small fish market

where the smells of fresh fish competed with the garden perfume of lettuce,

celery, leeks and radishes.

There was also nearby a small fish market

where the smells of fresh fish competed with the garden perfume of lettuce,

celery, leeks and radishes. Aita worked there as secretary to the Basque Minister of Justice,

Jesus Maria Leizaola. In addition,

he and Mercedes traveled several times to

Aita worked there as secretary to the Basque Minister of Justice,

Jesus Maria Leizaola. In addition,

he and Mercedes traveled several times to

The Basques in

The Basques in  Ama had lost all their possessions. She cried alone at night. The only thing left to do now was to

look after her two baby daughters and to wait for news from her husband. When he got to

Ama had lost all their possessions. She cried alone at night. The only thing left to do now was to

look after her two baby daughters and to wait for news from her husband. When he got to  Aita and Ama waited in

Aita and Ama waited in  Before they left

Before they left

Meanwhile Mirentxu and Begona remained in the Basque Country staying

with their uncle, aunts and grandparents.

Here are the two girls with their Tio Ino Iribarren, Ama’s

brother, (in

Meanwhile Mirentxu and Begona remained in the Basque Country staying

with their uncle, aunts and grandparents.

Here are the two girls with their Tio Ino Iribarren, Ama’s

brother, (in

By the beginning of the twentieth century the warring factions had

resolved most of their principal grievances and began to settle down into the

Uruguayan version of two-party electoral politics. The “Whites”

(“Blancos”) were the conservative party representing the largely

rural population and the Church; the “Reds” (“

By the beginning of the twentieth century the warring factions had

resolved most of their principal grievances and began to settle down into the

Uruguayan version of two-party electoral politics. The “Whites”

(“Blancos”) were the conservative party representing the largely

rural population and the Church; the “Reds” (“